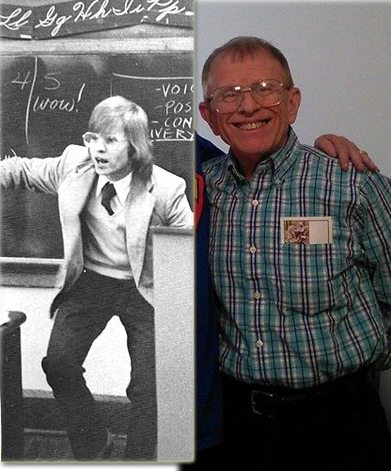

Up until my senior year, every play that I performed in at Grand Valley High School was directed by David Laster. He was a smirking, puckish character with a gravelly, smoke-stained voice and razor wit. He was filled with a passion for literature and theatre and he was a fierce protector of the artsy misfits of Grand Valley, Ohio.

We were a small school and, so, our performance space was our school’s basketball court with temporary folding chairs lined up in rows. But, if you have a Mr. Laster to direct, those handfuls of temporary performances can sink deep into your heart and remain lasting memories.

We didn’t have wireless mics. We didn’t really have mics at all. We had to project. The shells of our stagelights were made from large aluminum cans that shorted from time to time. I think we all used the same makeup kit. And we’d all have brownish lips and little red dots under our eyes (that I think we’re supposed to help the audience see our eyes better, but in years of performing after high school, I never experienced that phenomenon again). All of this was lovingly orchestrated by Mr. Laster. He encouraged people who, otherwise may have never thought to be involved in theatre, to join in and have some sense of community. Some sense that their voices not only fit in a world, but that they were needed in that world. He gave people chances.

He even gave people second chances. As a freshman, the first show I was in was Arsenic and Old Lace. I played some Irish cop and showed up in every scene with a cop partner. We asked Mr. Laster if we could eat powdered donuts because we thought that would be funny (I know – classic, right?). But, on closing night, we had a juvenile-fueled powdered donut fight backstage and shoved as many donuts into our mouths as we could before going onstage and, then, broke and giggled our way through our last scene. Mr. Laster was furious as he had every right to be. We weren’t respecting the material or ourselves. We were resorting to throwing away everyone’s hard work for a laugh. We apologized, but it felt terrible to let Mr. Laster down.

But, you know what? He gave me another chance the very next time I auditioned. And I tried not to let him down again. Over the years, I saw him give many students second chances. If he knew you had it in you (and he could count on you not to make the same mistakes), he would put his faith in you. And, speaking from being the benefactor of a second chance, I can say that that kind of faith and trust in a person helps them believe in themselves, too.

You don’t meet many people like Mr. Laster. Once, after talking with him, I turned and started walking down the hall. He stopped me and asked me to walk back. And, as I walked back, he looked at my feet the whole time and said, “I never noticed you walked like that.” I’m pigeon-toed and my feet point in as I walk. It’s not something that’s really held me back in any way. But, it’s certainly a different type of walk that sticks out. I quickly responded by saying, “The doctors told my Mom that I would grow out of it and didn’t need braces as a kid.” I, of course, didn’t grow out of it. And my response was what I was used to saying. It’s what I thought people wanted to hear. That I had tried to correct it and there was nothing that could be done. But, Mr. Laster simply said, "It’s nice to see. People are always trying to fix things that don't need to be fixed. Too many people walk the same.”

His last year directing was my junior year and, for his final show, he picked The Night Thoreau Spent In Jail, the story of Henry David Thoreau’s awakening to march to the beat of his own drummer. It was Mr. Laster’s swan song. I got to be Ralph Waldo Emerson and I can honestly say it was the singular experience that cemented my decision to pursue a career in the arts.

I'm grateful that I got a chance to thank him while he was alive for guiding me into theatre and storytelling (and to, again, apologize for the powdered donut incident). He answered by apologizing for "corrupting" me. And he said it with that familiar smirk that let me know he not only heard me, but that he whole-heartedly understood me.

Much love to you, Mr. Laster. You were a wonderful teacher, friend, shepherd and protector to all who etched our names on the old costume closet wall.

You will be truly missed, but I am truly glad you were here.

We were a small school and, so, our performance space was our school’s basketball court with temporary folding chairs lined up in rows. But, if you have a Mr. Laster to direct, those handfuls of temporary performances can sink deep into your heart and remain lasting memories.

We didn’t have wireless mics. We didn’t really have mics at all. We had to project. The shells of our stagelights were made from large aluminum cans that shorted from time to time. I think we all used the same makeup kit. And we’d all have brownish lips and little red dots under our eyes (that I think we’re supposed to help the audience see our eyes better, but in years of performing after high school, I never experienced that phenomenon again). All of this was lovingly orchestrated by Mr. Laster. He encouraged people who, otherwise may have never thought to be involved in theatre, to join in and have some sense of community. Some sense that their voices not only fit in a world, but that they were needed in that world. He gave people chances.

He even gave people second chances. As a freshman, the first show I was in was Arsenic and Old Lace. I played some Irish cop and showed up in every scene with a cop partner. We asked Mr. Laster if we could eat powdered donuts because we thought that would be funny (I know – classic, right?). But, on closing night, we had a juvenile-fueled powdered donut fight backstage and shoved as many donuts into our mouths as we could before going onstage and, then, broke and giggled our way through our last scene. Mr. Laster was furious as he had every right to be. We weren’t respecting the material or ourselves. We were resorting to throwing away everyone’s hard work for a laugh. We apologized, but it felt terrible to let Mr. Laster down.

But, you know what? He gave me another chance the very next time I auditioned. And I tried not to let him down again. Over the years, I saw him give many students second chances. If he knew you had it in you (and he could count on you not to make the same mistakes), he would put his faith in you. And, speaking from being the benefactor of a second chance, I can say that that kind of faith and trust in a person helps them believe in themselves, too.

You don’t meet many people like Mr. Laster. Once, after talking with him, I turned and started walking down the hall. He stopped me and asked me to walk back. And, as I walked back, he looked at my feet the whole time and said, “I never noticed you walked like that.” I’m pigeon-toed and my feet point in as I walk. It’s not something that’s really held me back in any way. But, it’s certainly a different type of walk that sticks out. I quickly responded by saying, “The doctors told my Mom that I would grow out of it and didn’t need braces as a kid.” I, of course, didn’t grow out of it. And my response was what I was used to saying. It’s what I thought people wanted to hear. That I had tried to correct it and there was nothing that could be done. But, Mr. Laster simply said, "It’s nice to see. People are always trying to fix things that don't need to be fixed. Too many people walk the same.”

His last year directing was my junior year and, for his final show, he picked The Night Thoreau Spent In Jail, the story of Henry David Thoreau’s awakening to march to the beat of his own drummer. It was Mr. Laster’s swan song. I got to be Ralph Waldo Emerson and I can honestly say it was the singular experience that cemented my decision to pursue a career in the arts.

I'm grateful that I got a chance to thank him while he was alive for guiding me into theatre and storytelling (and to, again, apologize for the powdered donut incident). He answered by apologizing for "corrupting" me. And he said it with that familiar smirk that let me know he not only heard me, but that he whole-heartedly understood me.

Much love to you, Mr. Laster. You were a wonderful teacher, friend, shepherd and protector to all who etched our names on the old costume closet wall.

You will be truly missed, but I am truly glad you were here.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed