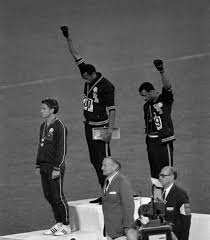

Today is the anniversary of this iconic protest at the 1968 Summer Olympic Games in Mexico City.

In America, it's common for us to bring up the 1936 Summer Olympics in Berlin when talking about our place in Human Rights and the Olympics. Jesse Owens, Ralph Metcalfe and Mack Robinson shattered the myth of aryan racial supremacy by dominating the 100 and 200 meter races. It puts us at the forefront of equality (if we conveniently ignore the fact that those three medalists came home to Jim Crow laws in the South).

But, we don't often shine a positive light on the 1968 Olympics. These two American men standing on the podium after the 200-meter sprint final, gold medalist Tommie Smith (who had just shattered the Olympic record time) and bronze medalist John Carlos, are often mistakenly thought to be raising their fists in militant disrespect.

And I suppose that depends on your definition of militant. Was it combative? Absolutely. Violent? Maybe to closed minds that didn't want other closed minds to see a protest displayed before the world. What I don't think you can deny is that it was not a sign of disrespect but of absolute and all-encompassing respect.

This was 1968. Over 2 decades after Jackie Robinson broke through the color barrier in Major League Baseball, 4 years after the Civil Rights Act of 1964 banned discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex or national origin in employment practices and public accommodations. But, Tommie Smith, John Carlos and other athletes of color were not being treated the same as their white peers. There were still public restrooms and water fountains they were not permitted to use and hotels they were not allowed to stay in. POC all over our glorious democracy were being prohibited (often violently) from voting, from jobs, from better housing and schools. Young men of color were being sent to Vietnam and fighting and dying for their country on foreign soil and coming home to suffer inequalities their white brothers in arms were not subjected to. Peaceful protests on city streets for equality and simple liberties were being met with taunts, with fists, with stones, with bullets, with high-pressured hoses, with police batons and attack dogs. Innocent lives were lost. Public figures like Martin Luther King and Robert Kennedy who spoke up for them were being gunned down. If you wanted a recipe for a need for militancy, that's as good as they get.

But, neither of these men were affiliated with a militant group. They were members of the Olympic Project for Human Rights (OPHR), a multi-race organization of American athletes. And what they opposed was the glossing over of human rights abuses across the globe. In 1968, just before the Olympics, students protested in Mexico City demanding that the country that could afford to host the Olympic games could afford to address the rampant poverty of many of its citizens. The corrupt Mexican government met this protest with fierce brutality that resulted in anywhere between 200 and 2000 deaths. The official number was covered up as were the slums of the city that bordered the airport. Huge signs and billboards of Olympic pride were literally put up all around the perimeter of the airport so that incoming athletes and guests would not see the slums and poverty.

This was what the OPHR protested. At first, their goal was a boycott of the entire Olympic games. But, since consensus could not be met for an all-out boycott, it was decided that each athlete should decide for him/herself how to best demonstrate.

The International Olympic Committee's president, Avery Brundage, not only did nothing to confront the abuse of the Mexican government leading up to the Olympics, he also officially banned any form of protest from the OPHR.

This was the “peaceful” display of global humanity through athletics that John Carlos and Tommie Smith entered when they arrived in Mexico City. And this is what they decided to do. They brought black gloves (Carlos had accidentally left his so they wound up each wearing one) and walked out to the podium shoeless, wearing black socks. They also wore beads and a scarf to protest lynchings. This was their "militant" protest against poverty and racism and disrespect and a global turning of the eye to bigger victories that needed to be won. They raised their fists knowing that that could very well be the end of their track careers. They knowingly raised their fists after receiving multiple personal death threats.

No one else knew what they were about to do before they stepped up to the podium. No one else, that is, but Peter Norman. Having just broken the Australian 200-meter record to win the silver medal, he waited with Smith and Carlos to be ushered onto the podium. Carlos and Smith told Norman what they were planning to do during the ceremony and, as Australian journalist, Martin Flanagan wrote:

"They asked Norman if he believed in human rights. He said he did. They asked him if he believed in God. Norman, who came from a Salvation Army background, said he believed strongly in God. We knew that what we were going to do was far greater than any athletic feat. He said, 'I'll stand with you'. Carlos said he expected to see fear in Norman's eyes. He didn't; 'I saw love.'"

Norman had seen similar racism in Australia to peaceful protests from the oppressed indigenous peoples of his country and he knew that this was not only his fight, too, that this should be everyone's fight.

So, Carlos grabbed an OPHR badge from a member of the US rowing team and pinned it on Norman. And the three of them, champions from different backgrounds, different nationalities and different ethnicities stood on a podium of three different levels and formed an immediate and ever-lasting friendship and brotherhood as equals.

The International Olympic Committee called this protest, "a deliberate and violent breach of the fundamental principles of the Olympic spirit." But, it should be noted that, going back to the iconic 1936 Olympics in Berlin, the International Olympic Committee had no problem with the Nazi salute.

John Carlos and Tommie Smith were forced to leave Mexico City and were suspended from the US Track Team. Smith's Olympic record would stand until 1984. For wearing that OPHR badge in unity with Carlos and Smith, Peter Norman was also shunned and his track career suffered. In 2000, when the Summer Olympic were held in Sydney, Norman was not invited to be included with all of the great past Australian medal winners even though his 1968 Olympic time still stands to this day as the Australian record for the 200 meter sprint.

But, when Norman died in 2006, Carlos and Smith were pallbearers at his funeral.

This story is at the heart of what the Olympics are meant to be.

First Posted On Facebook.

In America, it's common for us to bring up the 1936 Summer Olympics in Berlin when talking about our place in Human Rights and the Olympics. Jesse Owens, Ralph Metcalfe and Mack Robinson shattered the myth of aryan racial supremacy by dominating the 100 and 200 meter races. It puts us at the forefront of equality (if we conveniently ignore the fact that those three medalists came home to Jim Crow laws in the South).

But, we don't often shine a positive light on the 1968 Olympics. These two American men standing on the podium after the 200-meter sprint final, gold medalist Tommie Smith (who had just shattered the Olympic record time) and bronze medalist John Carlos, are often mistakenly thought to be raising their fists in militant disrespect.

And I suppose that depends on your definition of militant. Was it combative? Absolutely. Violent? Maybe to closed minds that didn't want other closed minds to see a protest displayed before the world. What I don't think you can deny is that it was not a sign of disrespect but of absolute and all-encompassing respect.

This was 1968. Over 2 decades after Jackie Robinson broke through the color barrier in Major League Baseball, 4 years after the Civil Rights Act of 1964 banned discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex or national origin in employment practices and public accommodations. But, Tommie Smith, John Carlos and other athletes of color were not being treated the same as their white peers. There were still public restrooms and water fountains they were not permitted to use and hotels they were not allowed to stay in. POC all over our glorious democracy were being prohibited (often violently) from voting, from jobs, from better housing and schools. Young men of color were being sent to Vietnam and fighting and dying for their country on foreign soil and coming home to suffer inequalities their white brothers in arms were not subjected to. Peaceful protests on city streets for equality and simple liberties were being met with taunts, with fists, with stones, with bullets, with high-pressured hoses, with police batons and attack dogs. Innocent lives were lost. Public figures like Martin Luther King and Robert Kennedy who spoke up for them were being gunned down. If you wanted a recipe for a need for militancy, that's as good as they get.

But, neither of these men were affiliated with a militant group. They were members of the Olympic Project for Human Rights (OPHR), a multi-race organization of American athletes. And what they opposed was the glossing over of human rights abuses across the globe. In 1968, just before the Olympics, students protested in Mexico City demanding that the country that could afford to host the Olympic games could afford to address the rampant poverty of many of its citizens. The corrupt Mexican government met this protest with fierce brutality that resulted in anywhere between 200 and 2000 deaths. The official number was covered up as were the slums of the city that bordered the airport. Huge signs and billboards of Olympic pride were literally put up all around the perimeter of the airport so that incoming athletes and guests would not see the slums and poverty.

This was what the OPHR protested. At first, their goal was a boycott of the entire Olympic games. But, since consensus could not be met for an all-out boycott, it was decided that each athlete should decide for him/herself how to best demonstrate.

The International Olympic Committee's president, Avery Brundage, not only did nothing to confront the abuse of the Mexican government leading up to the Olympics, he also officially banned any form of protest from the OPHR.

This was the “peaceful” display of global humanity through athletics that John Carlos and Tommie Smith entered when they arrived in Mexico City. And this is what they decided to do. They brought black gloves (Carlos had accidentally left his so they wound up each wearing one) and walked out to the podium shoeless, wearing black socks. They also wore beads and a scarf to protest lynchings. This was their "militant" protest against poverty and racism and disrespect and a global turning of the eye to bigger victories that needed to be won. They raised their fists knowing that that could very well be the end of their track careers. They knowingly raised their fists after receiving multiple personal death threats.

No one else knew what they were about to do before they stepped up to the podium. No one else, that is, but Peter Norman. Having just broken the Australian 200-meter record to win the silver medal, he waited with Smith and Carlos to be ushered onto the podium. Carlos and Smith told Norman what they were planning to do during the ceremony and, as Australian journalist, Martin Flanagan wrote:

"They asked Norman if he believed in human rights. He said he did. They asked him if he believed in God. Norman, who came from a Salvation Army background, said he believed strongly in God. We knew that what we were going to do was far greater than any athletic feat. He said, 'I'll stand with you'. Carlos said he expected to see fear in Norman's eyes. He didn't; 'I saw love.'"

Norman had seen similar racism in Australia to peaceful protests from the oppressed indigenous peoples of his country and he knew that this was not only his fight, too, that this should be everyone's fight.

So, Carlos grabbed an OPHR badge from a member of the US rowing team and pinned it on Norman. And the three of them, champions from different backgrounds, different nationalities and different ethnicities stood on a podium of three different levels and formed an immediate and ever-lasting friendship and brotherhood as equals.

The International Olympic Committee called this protest, "a deliberate and violent breach of the fundamental principles of the Olympic spirit." But, it should be noted that, going back to the iconic 1936 Olympics in Berlin, the International Olympic Committee had no problem with the Nazi salute.

John Carlos and Tommie Smith were forced to leave Mexico City and were suspended from the US Track Team. Smith's Olympic record would stand until 1984. For wearing that OPHR badge in unity with Carlos and Smith, Peter Norman was also shunned and his track career suffered. In 2000, when the Summer Olympic were held in Sydney, Norman was not invited to be included with all of the great past Australian medal winners even though his 1968 Olympic time still stands to this day as the Australian record for the 200 meter sprint.

But, when Norman died in 2006, Carlos and Smith were pallbearers at his funeral.

This story is at the heart of what the Olympics are meant to be.

First Posted On Facebook.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed